Find Happiness and Success By Changing Negative Self-beliefs

Eleven-year-old children showed me how they developed negative self-beliefs that worked against their highest good, and how they can be changed.

The following paragraph under the heading “The Whole Child” changed the course of my life when I chanced to pick up a flyer at an international conference on community education in 1979:

We devote a lot of time to adult policies, trying to make a better world. But every reform is frustrated or perverted. The quality of life is not improved, because the people are the same. What changes people? Well any one adult can recuperate from his childhood if he is dedicated to go through sufficient personal torment. But the population will generally behave according to their upbringing. The greatest power over human life is parent power. How you raise a person has a more potent effect on their ability to achieve happiness than any other influence or circumstance.

~ Fitzroy Community School, Melbourne

As a parent and teacher the paragraph begged the question, “How does a child cease to be ‘whole’?’

If there is a unifying glue of integrity that makes us whole, what happens to weaken this glue and cause some children to split apart, to become fragmented personalities unable to grow into ‘whole’ integrated adults who fail, often despite their best efforts, to improve the quality of their lives, or even to achieve lasting happiness and success? A class of eleven-year-old students in Queensland answered this question for me – seven years after first reading the flyer.

They were the worst class in the school when I took over from the vice-principle who went on long-service leave. Because they found it difficult to settle in the classroom each morning I began the day with aerobic exercises, a run around the oval, and fun relays with balls. With a chance to blow off steam, the rest of the day flowed relatively smoothly. However, one morning they would not settle. Almost in exasperation I asked, “What happened before you got to school?” This is what I discovered that morning and the following weeks...

With tears streaming down his cheeks, [Peter] told me that before he came to school his mother called him “a fat slob.” He had tried to diet. He hated being called fat and he hit out viciously at his schoolmates in anger.

[Susan] also cried. Her father had yelled at her and called her “a clumsy oaf.” She felt she could never get anything right and drew beautiful horse pictures instead of doing her work.

[Tracey] was constantly out of her seat, pinching and hitting the boys. She wore a permanent “I don’t care” attitude on her sullen face. Her extremely short attention span made her work scrappy. Her self-image was very low. At home she had to contend with a stepfather who constantly taunted her about wearing a bra and, like an immature and annoying teenager, repeatedly pulled the elastic on the back of it.

[Greg] was taller then me, yet walked like a toddler about to trip over his feet. His favourite words were, “Eh, eh!” and he scribbled them all over his books, and the blackboard when no one was looking. He annoyed everyone in class and was constantly told he was “stupid.” And he acted it. I still remember the hate in his clear blue eyes when I asked him to have a chat with me one recess about what was upsetting him. He told me his father had multiple sclerosis and when he wanted to help around the house, his father rejected his offer and said he wanted to do things himself. His mother worked in the city and didn’t get home until late. Tears filled his eyes when he told me how much he missed her.

[Jenny] was often unsettled and sometimes found it difficult to get along with her classmates. Inside she was emotionally torn apart because she wanted to live with her mother instead of her father and stepmother. However her mother was addicted to drugs and unable to give her the love and care she needed.

[Joanne] cried herself to sleep each night, and had done so for four years, because her father rarely let her see her mother after their divorce. She shared with me a beautiful story she wrote about a picnic, which turned out to be the day her parents broke up. She felt powerless to change the situation and lived in chronic grief.

Fully one-third of the class came from broken homes. While one girl talked about the benefits of having two families, the rest of the children were clearly unhappy about the loss of one of their parents. Many were still upset over having to go through the experience of a custody dispute. Some were adversely affected by continuing bitterness between parents, and being put in the position of having to take sides.

These were also my childhood experiences. At that time I was then in my late thirties and had not recovered from my own parents’ bitter divorce when I was eleven-years-old. What my students confronted me with, therefore, was a rude awakening of mammoth proportions.

I can tell you that this was the tip of the proverbial iceberg, and there was a lot of damage to undo. Not only that, but some children also carried leftover problems from previous teachers. When [Simone] asked for extra help with maths she told me that I was the first teacher she had ever been “game enough to ask for help from” because she was “scared they would yell at me if I said I couldn’t do something.” Upon investigation [Simone’s] previous teacher told me that although she was a lovely girl, she was a slow learner who would never do well at maths.

Really?

Just consider all the false beliefs these children developed about themselves from these unhealthy experiences. They may appear of minor importance to an adult, but to a child they can do lasting damage. When I questioned how had I coped with similar experiences as a child, I understood how I shut down my feelings and hid in my intellect. One day I even caught myself saying, “I will just have to harden my heart and go on.”

What does this do? To begin with, it wipes out our ability to feel empathy and compassion. It steers us away from trying to understand the situation we are in, and entraps us within a black and white world where we are unwilling to look at things in shades of grey or from different perspectives. We can also do unto others – with conscious or unconscious intent – what was done to us or remain a victim of our fate and become resentful and bitter. For me, one way of coping, of stopping my personality from fragmenting further, was to compulsively take care of other people’s needs while denying my own.

What I learned from my students was the jolt I needed to start listening to the still traumatised eleven-year-old within me who was left to her own devices to cope as best she could after her parents had emotionally fallen apart. Aware of the struggle many of my students were going through, I thought about changes I could make to my teaching practice to help them overcome some of their adverse experiences.

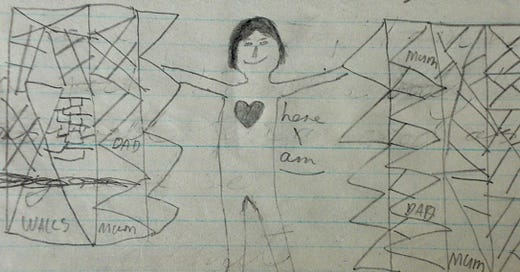

To this end the creative arts was the most powerful tool I had. Since children use play to integrate their experiences, I decided to explore how creative drama could help unlock the beautiful child within them as a counter measure to what they had begun believing about themselves. And it opened my eyes as to what I needed to do when I began to face my own “personal torment.” Exactly what this would entail I had no idea until I improvised one day with a drama lesson. I began, as usual, with the room cleared of all desks and the chidlren lying in a relaxed state on the carpeted floor. It was one of those days when it seemed that someone else was speaking through me:

“During the time we have been together I have caught glimpses of the beautiful person many of you have hidden deep within yourselves. We are all born with this beauty, but each time we’re hurt, we place a layer of protection over it to shut out people who hurt us. With each layer we add, it becomes more difficult to see this inner beauty. All these layers become armor that protects you, much like the armor the knights of old clanked around in. But wearing so much armor they were clumsy on their feet and found it difficult to walk around. It limited their movements just like our protective armor limits our growth and development today. But all this armor isn‘t the real you at all.”

A few children began to get restless. Some opened their eyes and stared at the ceiling. I thought that if I could get through to a quarter of them I would have achieved something.

“I’m going to play some soft music. When you feel ready, stand up and move very slowly to create a shape with your body. Then let it melt slowly into another shape, and so on. As you change each shape I want you to visualize casting off a layer of the armor – sort of like peeling layers off an onion – until you can remove all the layers to discover the beautiful you inside. I want you to continue making body shapes while you get to know that part of you. If you think this is too difficult to do right now, just concentrate on making interesting shapes. Perhaps you could turn yourselves into things or people you might prefer to be.”

In time to the music, the children’s movements began to resemble flowers gradually opening in the warm rays of the sun. The changing of shapes created the illusion of a gentle wind playing with petals. Concentration was high, bodies bent or swayed slowly, many arms reached up into the air, faces were solemn...serious.

From the excited sharing that followed I could see that the exercise had a profound transformational impact on many of the girls. Some wrote stories about the feelings it brought up. Others wrote plays about what they were experiencing at home. Many of the girls requested that they enact a custody case in court.

Some of the boys were less responsive. Many of them had shut down their feelings so they would not experience the emotional pain they refused to acknowledge. They were far from ready to venture into any ‘personal torment’ if they could help it. I discovered why after I went to see a psychiatrist who began asking probing questions about my own childhood. I can sum up the “personal torment” in two words: toxic shame. And I did not want to go there as it set off all my self-defence alarm bells and I retreated into my head.

Now, if some enlightened person had told me that toxic shame had to do with an erroneous belief that I was “bad” because of all the bad things that had happened to me that I must have ‘deserved’ because I was so flawed I could never make myself better, it might have made it easier for me to start delving into my past with courage and an open mind instead of putting up bulwarks of self-defence and going into hiding. Toxic shame is quite a different feeling from the healthy of shame that comes when we do something we know is wrong; toxic shame is a belief that we are inherently ‘wrong’ or ‘bad’; it is an indelible stain we cannot wash out.

As a child, physical punishment meant I had done something wrong, so I associated bad things happening to me as some sort of punishment for being ‘bad’. In this way, any sort of abuse can be interpreted as punishment. The ‘good’ parent administers punishment to the ‘bad’ child. Sexual abuse can cause a child to feel dirty or yicky and bad inside. If no one rescues the child from this abuse and tells them that someone did something bad to them, they can internalise the bad feeling as a belief that they are inherently bad and deserve to be punished. This is toxic shame.

Family therapist, John Bradshaw, who coined the term ‘toxic shame’, wrote in his book, Reclaiming Virtue:

A misbehaving child reflects the existence of some need, deprivation, or detrimental influence. “Control the environment and not the child” is a fundamental principle of Montessori education.

In general, the adult personality, with its need for control, its perceptions, and its unresolved childhood issues, is the most detrimental element in the child’s environment.

The impact of my ability to listen to this class of distressed eleven-year-olds was huge. Their overall behaviour began to improve with a corresponding improvement in their academic achievement. [Greg] who would only write “eh, eh” over everything, became an avid reader and topped the class in some of the end-of-year tests. No longer did he walk like a toddler. He proved to be an interesting abstract thinker who enthusiastically began to join in class discussions that became a feature of our time together. [Simone], who had once struggled with maths, proudly wrote to me during her second year of high school to share that she had taken an advanced maths class and came dux, beating “a brainy boy.”

Teaching this class of eleven-year-olds nudged me onto a path of self-healing where I went through the “sufficient personal torment” to regain my feelings of love, empathy, compassion, ability to walk in someone else’s shoes and, the greatest gift of all, to feel inner peace. Looking back, I can easily see how my false beliefs about myself became the armour I clanked around in that hid my true self, and I had to remove it bit by painful bit until I could again become like the beautiful children I saw in my drama class opening out like flowers in the rays of early morning sun.

I remain grateful to this day for the precious gift my students gave me, and the light it shed on the path in life I needed to take.

You can read earlier posts from Juliet at Different Perspectives.

How am I the first person to live this piece?! This is beautiful and profound. I spent many years working with children. Laying on the floor with fabrics being floated above them, taking feeling journeys... This is a familiar and wonderful thing. How rare am environment where such a thing can happen. How could you possibly be allowed? How rare to stray from the standardized role.

I cannot say how much I love this piece. I have so much to think about and make new.